Antonio Gaudi, The Sagrada Familia and their Inspiration for Family Therapy

By Monica McGoldrick and Nydia Garcia Preto

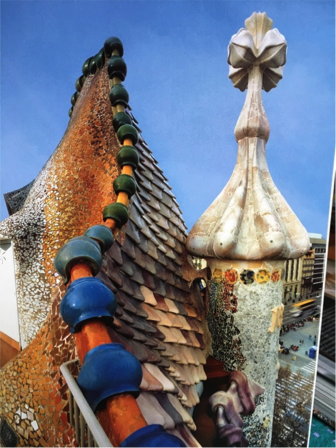

We discovered in the Spanish architect and artist Antonio Gaudi a phenomenal systemic inspiration for us as family therapists. He was one of the most creative architects who ever lived. He thought in a totally systemic way about human life and about our relationship with nature. His work and systemic and ecological thought are a model for us, who are trying to hold onto systemic perspectives for therapy. From childhood he seems to have been equally in love with nature and with the world of imagination, believing that our lives must always be about something larger than ourselves- especially about our connections to nature and to the world around us. . He had profound systemic awareness that what we create continues through the involvement of human beings with it. The theme of having been chosen for some larger purpose runs throughout his life (Hensbergen, 2001, p. 3), as it must for all of us who are trying to think systemically in our increasingly linear, materialistic, individually focused world Always ecologically focused, he saw the laws of nature not as an impediment, but as the primary resource for our creativity. He believed we must not waste our resources, but rather value, use and reuse them. In all his work he focused carefully on how his architecture would be interacted with by the people in the spaces and buildings he was creating. And he made a point of integrating all kinds of local materials, reusing bits and scraps of tile for his creations- drawing from whatever resources he could find around him.

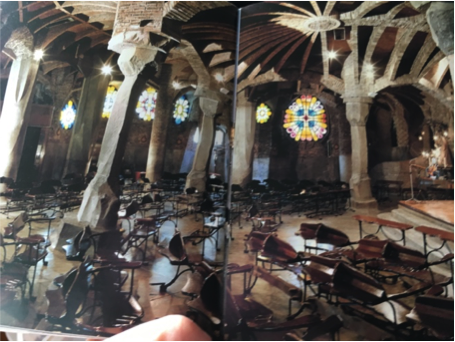

Gaudi strove for harmony and balance in every creation, always searching for a contrast of light and shade, concave and convex, continuity and discontinuity. He believed in following the paths of nature, creating columns that reflected not strict geometry but the bends of the trees and branches, just as we try to support the pathways of our patients, supporting them to find solutions that fit for them, rather than pressing them into our preferred solutions.

Gaudi never believed that his version of creativity was the ultimate standard. He was dedicated to those who worked for him, viewing their work as an essential part of his creativity and recognizing that they deserved great appreciation. Though he didn’t have formal students, was very generous in sharing with anyone who wanted to draw from his work or ideas.

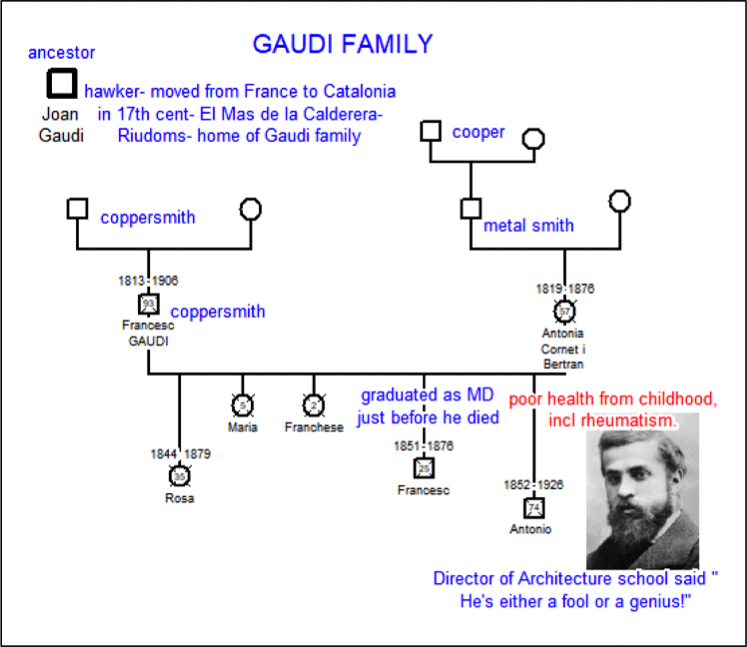

Antonio Gaudi was born of French ancestry in Catalonia in 1852. He came from a family of artistans. His father and grandfather were coppersmiths, his mother’s father was also a smith, and her grandfather was a cooper. (Hensbergen, 2001, p. 4)

Antonio Gaudi was born of French ancestry in Catalonia in 1852. He came from a family of artistans. His father and grandfather were coppersmiths, his mother’s father was also a smith, and her grandfather was a cooper. (Hensbergen, 2001, p. 4)

He was the youngest of 5 siblings, and the only one to survive past young adulthood. Two siblings died in childhood, while Gaudi’s surviving brother, with whom he grew up, died just after finishing medical school. The oldest sister died three years later.

Named Antonio for his mother, Antonia, Gaudi was sickly, developing arthritis as a child. His mother died when he was only 24, but he always took pride her belief that though his birth and childhood were difficult, he had battled always to live. He never married and was known to be reticent, reserved, and frugal. He lived many years with his father, who died at 93 in 1906 and a niece, Rosa, who died at 36 in 1912.

Having studied in Barcelona, Gaudi lived in or near there for the rest of his life and that is where he did most of his work.

He devoted the last 4 decades of his life to his magnificent Basilica, the Sagrada Familia, knowing even as he designed it, that he would never live to see it completed, but imagining that artists of the future would add to his creation in new inventive ways that might take generations to complete. Even now, almost 100 years after Gaudi’s death the basilica is not even half completed. Gaudi’s vision for Sagrada Familia, was to create a spiritual forest, combining light and shade, gorgeous stone, glass and sculptures into a magnificent geometric spectacle of shape, color and feeling from all angles and at all hours of day and in all seasons. In the end he actually moved into his workshop at the Sagrada.

After Gaudi’s death he and his work seemed to be forgotten- as it sometimes seems is happening these days with family systems theory and practice. The artists Man Ray and Salvador Dali (another Barcelonian) tried without much success to promote appreciation for Gaudi’s work. But he and his magnificent creations were forgotten for decades.

However, by the 1950s, research and writings by Spanish and international critics spurred a renewed awareness of Gaudí’s incredible creativity. Gradually widespread international recognition of his work have evolved, culminating in 1984 in the listing of his key works as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Now, 100 years after Gaudi died The Sagrada Familia is visited by 3 million visitors annually, twice the population of the city of Barcelona. Artists from around the world are expanding on Gaudi’s creativity on The Sagrada, adding brilliant new ideas, colors and sculptures of their own invention, and it is planned that the building will be completed for the centenary of his death in 2026.

As in his lifetime he valued and cherished the artisans who worked with him, his work and ideas have now inspired numerous others, most famously Frank Gehry, whose Olympic Pavillion in Barcelona shows Gaudi’s inspiration clearly. Many others around the world have been inspired by Gaudi’s work. In 1999, American composer Christopher Rouse wrote the guitar concerto Concert de Gaudi, which won the 2002 Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition.

Gaudi trusted that future generations would respect, sustain and expand artistically and culturally the basic structures of nature that he worked so hard to breath into life.

Just as people have gradually come to appreciate Gaudi’s vision, creativity, spirit of collaboration, and his glorious respect for the laws of nature, to which future generations would add their own creativity and wisdom, we hope future generations will expand systemic theory and practice to help families in the future and to save our planet.